This is not Arizona. There is shade wherever I look. My view in every direction is obstructed by green. Much of it is the smooth green of tree leaves: the pale yellowish greens of sycamores, the bolder greens of maples and oaks. And there are the rougher, darker greens – the greens applied in primary school art projects with wet paint and sponges – of hemlocks and firs. Cutting through the green scrim are shingled roof lines.

If the neighborhood is a stage, the scrim is leafy and dark, with light overhead and shadows on the edges.

Today I am cutting diagonally across the stage from my house to town.

Pine cones and tree litter lie on the sidewalk. The sidewalks are often uneven, roiled by tree roots. In places sidewalks are made of old bricks. Their unevenness is pixilated. Where sidewalks are concrete the roots have cast whole sections into uneven planes. Because of the unevenness I must mind my step, and I become aware that the neighborhood appears to me in flashes, like fast cuts in a video, as I cast my eyes from houses and lawns back to the sidewalk. My gaze is as broken as a sidewalk.

The street is smoother, easier for walking, and many streets are quiet so I needn’t worry about cars. The sides of the street where people park are oil-stained from leaking old cars. Old cars are as common as old houses. There is an assortment of makes and models: old paint-dulled Hondas and Saturns, new BMWs and Saabs, mud spattered Subaru’s and even a few clunky, tank-like Land Rovers, the sort you see everywhere in Africa. They all seem to dribble oil. I suspect if you compared the streets of my neighborhood with those in other, newer parts of town, you’d find our streets more dribbled. This may speak to poverty, or preference in old cars, or the fact that relatively few houses in this neighborhood have working garages. The few garages I am aware of are converted to studios or apartments.

Yards are invested with flowers. I cannot name them all, do not know them all. I recognize hydrangeas, geraniums, lilies, roses, lambs’ ears, lavenders, rosemaries – all flowering. So the sunny places between the shadows are splashed with color. And vegetables: cabbages, corn, tomatoes, eggplants, and stands of beans and peas and basil and dill. There is nothing sterile about the lawns in this neighborhood – it’s not like one of those trim communities with crew-cut lawns and nothing growing in them but grass.

If you look you can see cats lurking in the dark shade of bushes.

Streets and houses are rimmed with stone. Stone walls. Stone borders. Stone foundations. Stone edges. Isolated boulders, like desert islands in a green sea. Piles of stone like burial cairns. Rock gardens. Artificial brooks. Riprap embankments. Piles of rocks beside piles of sand waiting for a mason’s shovel.

The walls are old, and a great number are cracked and whole sections lean forward under years of pressure from the contained soil of lawns and gardens. Frothy mounds of white phlox dangle over the edges. One house has painted its retaining wall a bluish gray, and also painted with the same high gloss industrial paint a line of stones in the grass marking the boundary with the neighbor’s yard, as if to improve on the color of the stone itself.

A number of porches are festooned with patriotic bunting. Many have ceiling fans. Some have lamps beside chairs and couches, even carpets, as if to move the living room outdoors.

A man, mid-thirties, sits in a lounge chair on one shaded porch talking on a cell phone while his dog, in a picketed yard, gazes up at him, head cocked, listening.

It is not until I emerge from the neighborhood and pass the downtown civic center with its big stone foundation that it dawns on me how much of an attempt builders have made to bring the surrounding mountains into the city. For the stones here echo the stones of forest floors and craggy cliffs, and the hemlocks and firs are in a sense ghosts of the surrounding woods, and even the houses with their shingled roofs and lush gardens suggest vacation cabins.

I wonder whether the intrusion of forest into city suggests a certain ambivalence about city life – how many of us have half a mind to live elsewhere, outside.

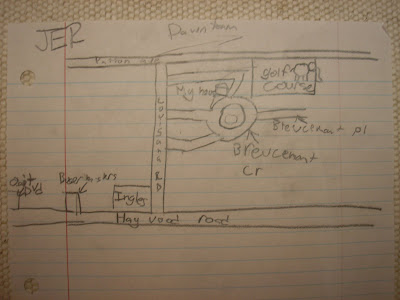

I was talking with a group of eighth graders at Asheville Middle School. The week before they’d made lists of places they visited in Asheville, and then marked those places on individual Google maps. The maps formed constellations representing their engagements with the city. We talked about them this week. At the end of our conversation I asked them to sketch their own maps of Asheville – the Asheville that wasn’t captured by the digital maps. Here are a couple examples of what they did. The most remarkable feature that I’ve noticed about these (as well as other hand-drawn maps that people have given me of Asheville) is they always include the drawer’s home. It makes sense, I suppose. It’s obvious. The home is the base from which other places flow. But I’ve not asked them to include it. Some do not even indicate streets, not at least in any realistic way. But they always include an indication of where they live. It seems a small but nontrivial point, perhaps basic to people’s mental configuration of space and place.

I was talking with a group of eighth graders at Asheville Middle School. The week before they’d made lists of places they visited in Asheville, and then marked those places on individual Google maps. The maps formed constellations representing their engagements with the city. We talked about them this week. At the end of our conversation I asked them to sketch their own maps of Asheville – the Asheville that wasn’t captured by the digital maps. Here are a couple examples of what they did. The most remarkable feature that I’ve noticed about these (as well as other hand-drawn maps that people have given me of Asheville) is they always include the drawer’s home. It makes sense, I suppose. It’s obvious. The home is the base from which other places flow. But I’ve not asked them to include it. Some do not even indicate streets, not at least in any realistic way. But they always include an indication of where they live. It seems a small but nontrivial point, perhaps basic to people’s mental configuration of space and place.